The Corryvreckan: Scotland’s legendary maelstrom between Jura and Scarba

Association Karukinka

Loi 1901 - d'intérêt général

Derniers articles

Suivez nous

Deep in the waters between the Scottish isles of Jura and Scarba lies one of nature’s most fearsome phenomena: the Corryvreckan whirlpool. This legendary maelstrom, known to mariners for over a millennium, represents far more than a navigational hazard—it embodies the raw power of Scotland’s coastal waters and the enduring struggle between human ambition and natural forces.

The Gulf of Corryvreckan, derived from the Gaelic Coire Bhreacain meaning “cauldron of the speckled seas” or “cauldron of the plaid,” stands as the third-largest whirlpool in the world. Located off Scotland’s west coast in Argyll and Bute, this narrow strait measuring just six cables at its narrowest point has earned a reputation that extends far beyond its modest geographical footprint.

Table of contents

The Geological foundations of fury

The Corryvreckan’s fearsome reputation stems from a unique combination of Atlantic currents and underwater topography that conspire to create one of Europe’s most violent tidal races. As flood tides enter the narrow channel between Jura and Scarba, they accelerate to speeds of 8.5 knots (16 km/h), encountering a seabed that reads like a maritime nightmare.

The underwater landscape reveals the source of Corryvreckan’s power: a deep hole plunging to 219 meters lies directly in front of a pyramid-shaped basalt pinnacle that rises dramatically from 70 meters depth to just 29 meters below the surface. This pinnacle, known ominously as “The Old Hag” (An Cailleach), forces the rushing tidal water upward in a massive surge that creates the whirlpool’s characteristic standing waves and vortexes.

When conditions align—particularly during spring tides with westerly winds—the Corryvreckan generates waves exceeding 30 feet (9 meters) and produces a roaring sound audible from 10 miles away. In extreme conditions, this maritime cacophony can reportedly be heard from distances up to 20 miles, creating what locals aptly describe as “Scotland’s maelstrom”.

Ancient chronicles and Royal Navy warnings

The Earliest historical records

The Corryvreckan’s dangerous reputation appears in written records spanning over 1,400 years. The earliest documented reference comes from Adomnan of Iona’s 7th-century “Life of St. Columba,” where the saint is described as having miraculous knowledge of a bishop who encountered the “whirlpool of Corryvreckan”. Intriguingly, Adomnan places this whirlpool near Rathlin Island, suggesting either geographical confusion or that the name originally applied to a different location.

The most vivid early description comes from Dean Donald Munro in 1549, who wrote with characteristic medieval frankness: “ther runnes ane streame, above the power of all sailing and rowing, with infinit dangers, callit Corybrekan. This stream is aught myle lang, quhilk may not be hantit bot be certain tyds”. Translated from Middle Scots, Munro warns that “there runs one stream, above the power of all sailing and rowing, with infinite dangers, called Corryvreckan. This stream is eight miles long, which may not be handled but by certain tides.”

Official naval classification

The Royal Navy’s relationship with Corryvreckan reflects the evolution of maritime safety protocols. While the main Gulf of Corryvreckan itself is not officially classified as unnavigable, the Admiralty’s West Coast of Scotland Pilot guide delivers an unequivocal warning: the waters are “very violent and dangerous” and “no vessel should then attempt this passage without local knowledge“.

The nearby Grey Dogs, or “Little Corryvreckan,” however, are classified as unnavigable by the Royal Navy. Experienced scuba divers who have explored these waters describe Corryvreckan as “potentially the most dangerous dive in Britain“, with one experiment involving a weighted dummy revealing the whirlpool’s power to drag objects down to depths of 262 meters (860 feet).

The Legends of King Breacan

When Norse mythology meets Scottish folklore

The whirlpool’s name carries the weight of ancient legend, most prominently the tale of King Breacan (or Bhreacan), a Norse or Danish prince whose story has been told in various forms for centuries. According to the most common version, Breacan sought to marry the daughter of a Scottish chief, who set him the seemingly impossible task of anchoring his vessel in the whirlpool for three days and three nights.

The prince consulted the Wise Men of Lochlin (Norway), who advised him to create three ropes: one woven from hemp, another from wool, and the third from the hair of pure maidens. The legend asserts that the purity of the maidens’ hair would render the final rope unbreakable.

Breacan’s fate was sealed by human frailty rather than natural force. On the first night, the hemp rope snapped; on the second, the wool rope failed. On the third night, the rope of maidens’ hair broke, and Breacan was dragged to his death. The tragic revelation came when one of the maidens confessed she had not been as pure as claimed, explaining the rope’s failure and Breacan’s doom.

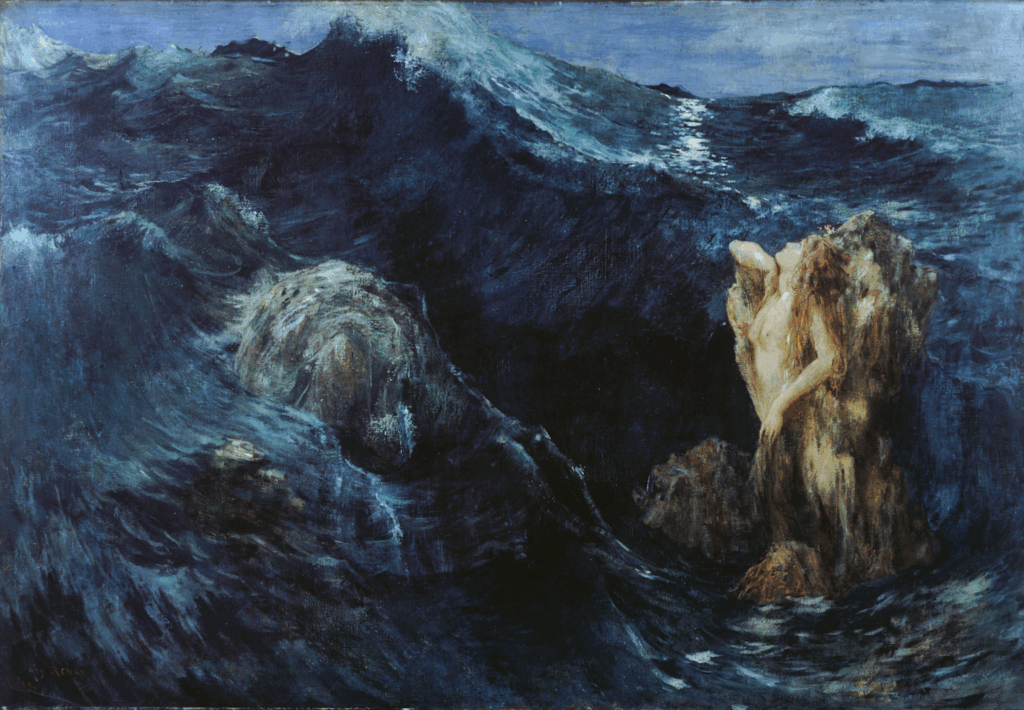

The Cailleach: Celtic Sea goddess

Parallel to the Norse legend runs the Celtic mythology of the Cailleach, the hag goddess of winter. Scottish folklore maintains that the Cailleach uses the Gulf of Corryvreckan as her washing tub, stirring the waters to clean her great plaid (a piece of tartan). When her clothes are clean, she hangs them to dry on the surrounding mountains, manifesting as snow-covered peaks.

This mythological framework transforms Corryvreckan from a mere geographical feature into a living entity, a place where the supernatural intersects with the natural world—a perspective that may have helped ancient mariners process the psychological impact of encountering such overwhelming natural forces.

George Orwell’s near-fatal encounter

The 1947 incident

Perhaps no single incident better illustrates Corryvreckan’s continuing danger to modern mariners than George Orwell’s near-drowning in August 1947. The future author of Nineteen Eighty-Four had retreated to the isolated island of Jura to complete his masterwork, living at Barnhill, a remote farmhouse accessible only by a five-mile walk.

On what should have been a routine fishing excursion, Orwell, accompanied by his three-year-old son Richard, nephew Henry Dakin, and niece Lucy Dakin, misread the tidal tables—a mistake that nearly cost him his life and deprived the literary world of one of its most influential works. The small dinghy was caught in the whirlpool’s grip during the flood tide, the most dangerous time to navigate these waters.

A mechanical failure that changed everything

As the boat was battered by the whirlpool’s edge, the outboard motor was wrenched from its mounting and fell into the sea—Orwell had failed to secure it with a chain, a seemingly minor oversight with nearly fatal consequences. Left with only oars against the Atlantic swells and whirlpool currents, the party faced what Orwell later confessed he thought would make them “goners”.

The group managed to row toward Eilean Mòr, a small rocky island, but the boat capsized as they attempted to land. Soaked, exhausted, and stranded on an uninhabited outcrop without supplies or means of communication, they faced exposure in the harsh Scottish climate. Their salvation came from passing lobster fishermen who spotted the smoke from a fire they had lit to keep warm.

Literary implications

Orwell recorded the incident in his diary with characteristic understatement: “On return journey today ran into the whirlpool & were all nearly drowned“. Some scholars suggest this traumatic encounter with death by drowning may have influenced the water imagery that pervades Nineteen Eighty-Four, particularly the scenes in Room 101 where fear of drowning becomes a tool of torture in the totalitarian state of Oceania.

Modern navigation challenges and safety protocols

Admiralty guidance for contemporary mariners

Modern navigation of the Corryvreckan remains governed by the same fundamental principles that challenged mariners centuries ago: timing, local knowledge, and respect for natural forces. The Admiralty’s current guidance emphasizes that the ideal transit time is during slack water at neap tides in calm weather conditions.

The recommended route follows the southern side of the gulf to avoid the most dangerous areas, particularly The Hag off the coast of Scarba. However, during west-going streams, the tidal flow sets strongly northward along Jura’s eastern shore before turning northwest into the gulf, making it difficult for vessels to maintain the safer southern route.

Tidal calculations and planning

The complexity of Corryvreckan’s tidal behavior stems from the different tidal ranges at each end of the gulf. At the eastern entrance, spring tide range reaches 1.5 meters, while the western end experiences 3.4 meters, with high water occurring 30 minutes earlier at the eastern end. These differentials create the pressure gradients that drive the violent currents through the narrow strait.

Professional mariners rely on detailed calculations considering not only tide tables but also barometric pressure, wind direction, and seasonal variations. The gulf’s behavior remains unpredictable enough that even experienced local sailors approach it with extreme caution.

Commercial and tourism operations

Despite its fearsome reputation, Corryvreckan has become a significant tourist attraction, with multiple operators offering boat trips from ports including Crinan, Port Askaig, and Craighouse. These operations run only during spring tides when the whirlpool effect is most pronounced, typically 50 times per season.

Tourist vessels maintain strict safety protocols, using rigid inflatable boats (RIBs) capable of handling the rough conditions while providing passengers with close-up views of the phenomenon. Modern GPS technology and weather monitoring allow operators to time approaches for maximum visual impact while maintaining safety margins.

The Corryvreckan as a scientific laboratory

Marine biology and underwater research

The intense currents flowing over the basalt pinnacle create a unique marine ecosystem. The constant upwelling brings nutrients from the depths, supporting rich filter-feeder communities including corals, sponges, and various shellfish species. This abundance, in turn, attracts larger marine life, including porpoises, dolphins, and whales.

For marine scientists, Corryvreckan represents a natural laboratory for studying extreme tidal environments. Research conducted by the Scottish Association for Marine Science in 2012 provided detailed observations of the whirlpool’s formation and behavior, contributing to broader understanding of similar phenomena worldwide.

Climate and oceanographic studies

The gulf’s unique position between the Atlantic Ocean and the more sheltered waters of the Inner Hebrides makes it a valuable site for oceanographic research. The mixing of different water masses here provides insights into larger oceanic circulation patterns and their response to climate change.

Scientists monitor the Corryvreckan as part of broader studies on how rising sea levels and changing weather patterns might affect coastal tidal races and their associated marine ecosystems. These studies have implications for understanding similar phenomena in other parts of the world.

Historical wrecks and maritime casualties

The PS Comet disaster of 1820

The waters around Corryvreckan have claimed numerous vessels over the centuries, with the most historically significant being the PS Comet in 1820. This pioneering steamship—the world’s first commercial passenger vessel—met its end near Craignish Point while attempting to reach the safety of Crinan Canal.

Captain Bain, navigating in challenging conditions with a strong southeast wind and failing light, encountered “a blinding snowstorm with accompanying mist” while approaching the dangerous waters near Corryvreckan. The vessel ran aground at Rudha na Traigh and, weakened by previous damage, split in two. The forward section with its historic machinery remained wedged on the rocks, while the stern section floated off toward the Corryvreckan and was never recovered.

Lessons in maritime safety

The Comet incident illustrates timeless principles of maritime safety that remain relevant today. The combination of deteriorating weather, failing light, strong tidal currents, and time pressure created a cascade of risks that overwhelmed even experienced mariners. Modern safety protocols emphasize the importance of contingency planning and conservative decision-making when approaching such dangerous waters.

Contemporary challenges and future considerations

Climate change implications

Rising sea levels and changing weather patterns associated with climate change may alter the gulf’s behavior in ways not yet fully understood. Scientists monitor these changes as part of broader studies on how coastal environments respond to global environmental shifts.

The increasing frequency of extreme weather events may make the whirlpool even more unpredictable, potentially affecting both commercial navigation and tourism operations. Long-term monitoring programs track these changes to inform future safety protocols.

Rescue service considerations

With ongoing budget pressures on emergency services in remote Scottish waters, the Corryvreckan presents particular challenges for maritime rescue operations. The combination of difficult sea conditions, remote location, and unpredictable timing of incidents requires specialized resources and training.

Modern rescue services rely on helicopter support, coastal rescue teams, and coordination with local fishing vessels familiar with the area’s conditions. However, the fundamental challenge remains the same as it was for ancient mariners: the need for rapid response in conditions that often prevent safe access.

The Enduring legacy of Scotland’s maelstrom

The Corryvreckan stands as a powerful reminder of nature’s capacity to humble human ambition and technology. From ancient Celtic legends to modern satellite navigation, this relatively small stretch of water has challenged every generation of mariners who have encountered it.

Its historical significance extends beyond maritime safety to encompass literature, mythology, and scientific understanding. For contemporary mariners, this strait represents the persistence of natural challenges in an age of technological sophistication. While GPS, weather radar, and modern safety equipment have improved survival odds, the fundamental lesson remains unchanged: respect for the sea’s power and the value of local knowledge passed down through generations of sailors.

The stories of King Breacan, George Orwell, and countless unnamed mariners who have tested themselves against these waters continue to resonate because they speak to universal themes of human ambition, natural limits, and the thin line between survival and catastrophe.

Whether approached as a scientific phenomenon, a navigation challenge, or a repository of cultural memory, the Corryvreckan whirlpool remains one of Scotland’s most compelling natural features—a place where ancient myths and modern realities converge in the eternal dialogue between humanity and the sea.

Views: 32

![[#7 – Ireland – Scotland 2024] From Loch Melfort to isle of Mull, via the Firth of Lorn](https://karukinka-exploration.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Moy-Castle_Lochbuie_Karukinka-e1720810021554-400x250.jpg)

![[#6 – Ireland – Scotland 2024] Stopover at Loch Melfort](https://karukinka-exploration.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Loch-Melfort_Karukinka_052024-3-400x250.jpg)

![[#5 Ireland – Scotland 2024] from Jura to Loch Melfort, via the Corryvreckan](https://karukinka-exploration.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/N-Islay_Jura_042024-11-400x250.jpg)

![[#4 Ireland – Scotland 2024] Scotland : Islay and Jura](https://karukinka-exploration.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/N-Islay_Jura_042024-29-400x250.jpg)

![[#3 Ireland – Scotland 2024] From Bangor (Belfast Lough) to Port Charlotte](https://karukinka-exploration.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IMG_3050-400x250.jpeg)

![[#2 Ireland – Scotland 2024] From Dublin to Bangor (Belfast Lough)](https://karukinka-exploration.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Donaghadee_0420242-400x250.jpg)